According to Chinchilla scaling laws for Transformers [1], data may soon be a bottleneck for training really large English language models. The vast majority of languages already lack data for training even moderately sized networks.

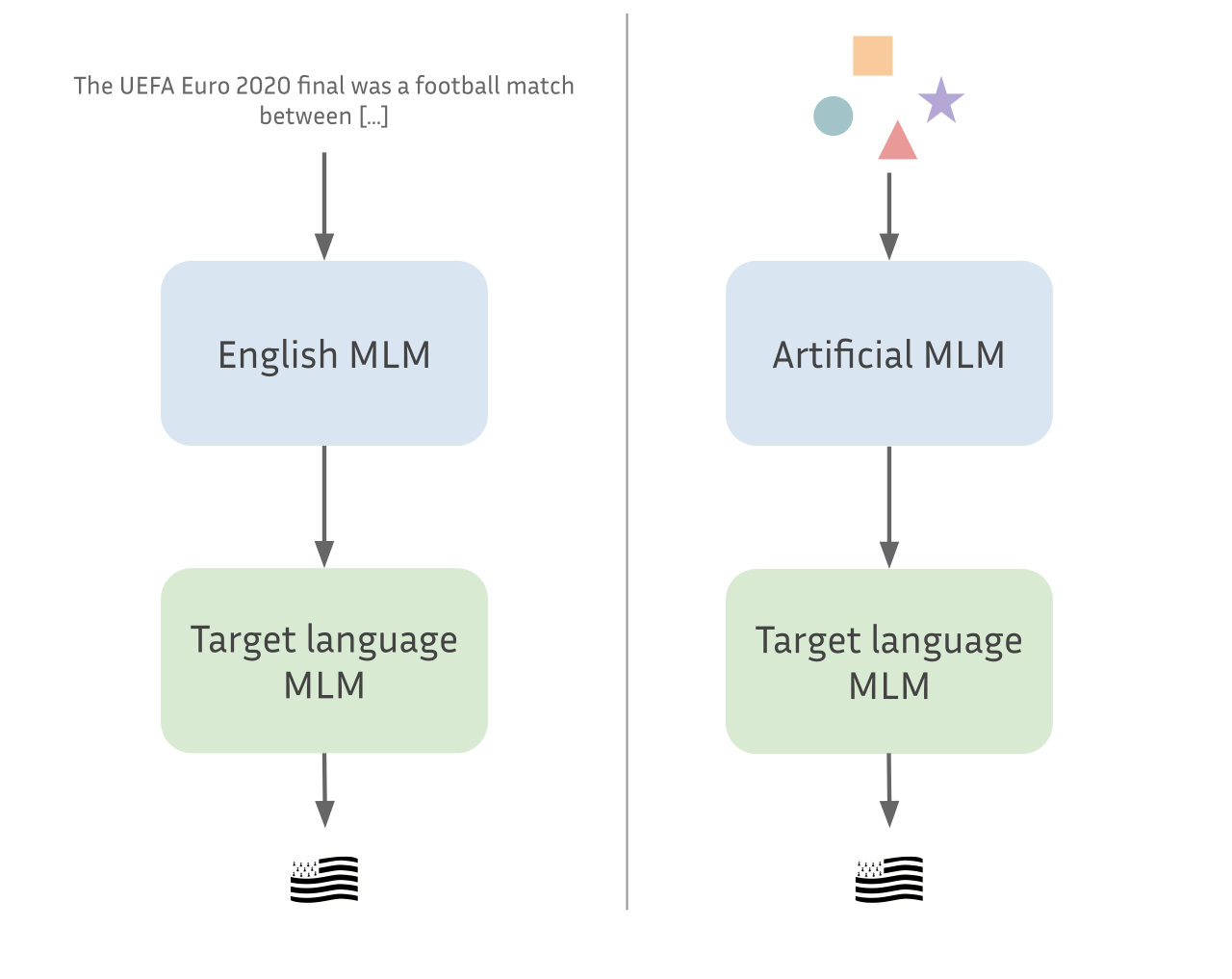

Thus, during the last few months, we experimented with the following question: what if we could pretrain Masked Language Models (MLM, think BERT or RoBERTa) using only artificially created data, then continue pretraining on languages with very little resources? Ideally, our synthetic data could be generated quickly and be scaled to extremely large sizes as well as have properties that allow the models to “learn something”.

Language Models trained on a source language can often transfer very well to a new language, even though the vocabulary is completely disjoint. Can we do the same with artificial data?

Yes, but how will it know what “New York” is?

The intent behind this work is not to entirely replace language data, but rather to see whether we can teach the networks to learn some simple operations before having to cope with semantics and meaning. Similar work was done for automatic summarization [2], showing that teaching a model to perform a few basic operations using synthetic data (e.g. copy one line) almost matches the performance of a fully pretrained model.

A secondary objective of this work is to understand what features are learnt from the training data by language models, and how much are they used when transferring to another language. Previous works [3] have shown that it was possible to pre-train a model on a different modality than text (e.g. music) and still transfer to natural language with great performance. What information is learnt that makes this transfer possible?

⚠️ Disclaimer: Our work falls into the “negative results” category. Nonetheless, we bumped into interesting questions and thought it would be nice to present our results informally here.

This work was done as part of my PhD supervised by Benoît Sagot and Éric de la Clergerie, funded by the PRAIRIE chair of Benoît Sagot.

The Method

We start by training Masked Language Models on “source” data, i.e. either natural language data or synthetic data (see below for the description of our synthetic data). For all our experiments, we work with encoder models similar to BERT with 12 layers and hidden size 768, processing sequences of length at most 128. We use batches containing 256 samples and train for 100k steps with AdamW, using a linearly decaying learning rate of at most 1e-4 and a warmup for the first 10k steps. This is a modest setup in terms of training but it enables us to experiment with new ideas pretty quickly.

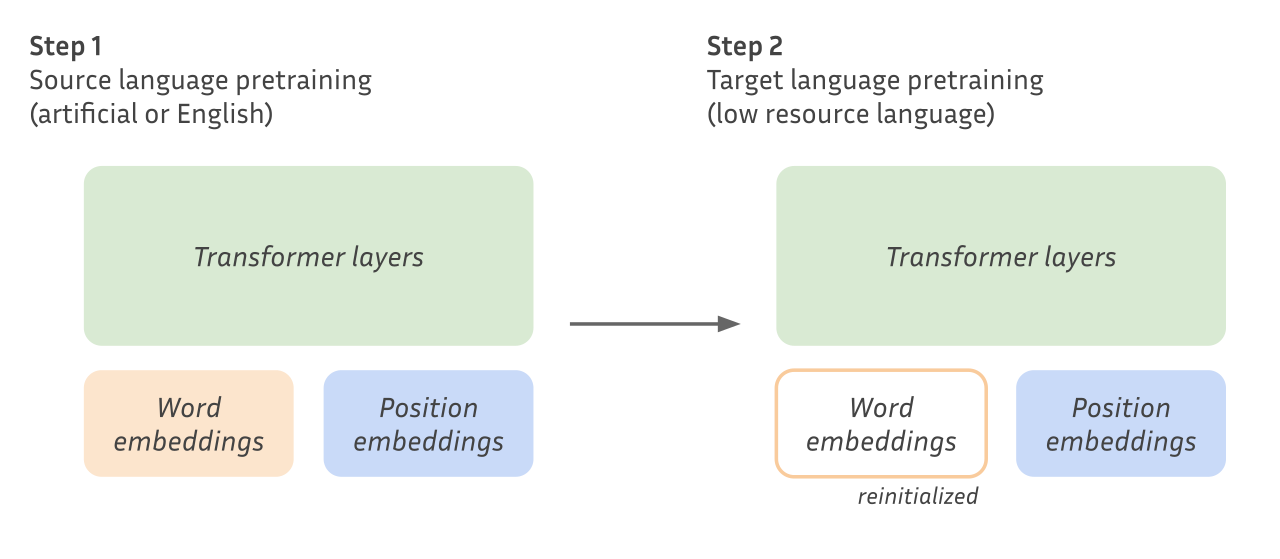

We then continue training on a target language. We keep all the source parameters except the embeddings (our source language has no vocabulary overlap with the target language) and retrain using the same hyperparameters except for the batch size which we reduce to 128 samples. We usually stop training around 50k iterations to save compute because the models have already started overfitting at that point.

We use the Breton subset of OSCAR 21.09 as our low-resource target language. It corresponds to around 5M tokens. In addition, Breton appears in the Wikiann NER dataset, which makes it possible to study finetuning setups.

We describe in the following section the source data we considered, including our synthetic language.

What we tried

Our methods

We try to identify a few key characteristics in natural data that should appear in our artificial language as well.

- Structure; natural data has a structure, whether it be images, text or sound. Since word embeddings are context-independent, we hypothesize that the structure is mainly modelled with the Transformer layers and the positional embeddings and that we should be able to transfer it to the target language.

- Co-occurrence; this is a very vague term encompassing a lot of higher concepts such as meaning. However, we think it may be important to learn making context-dependent decisions.

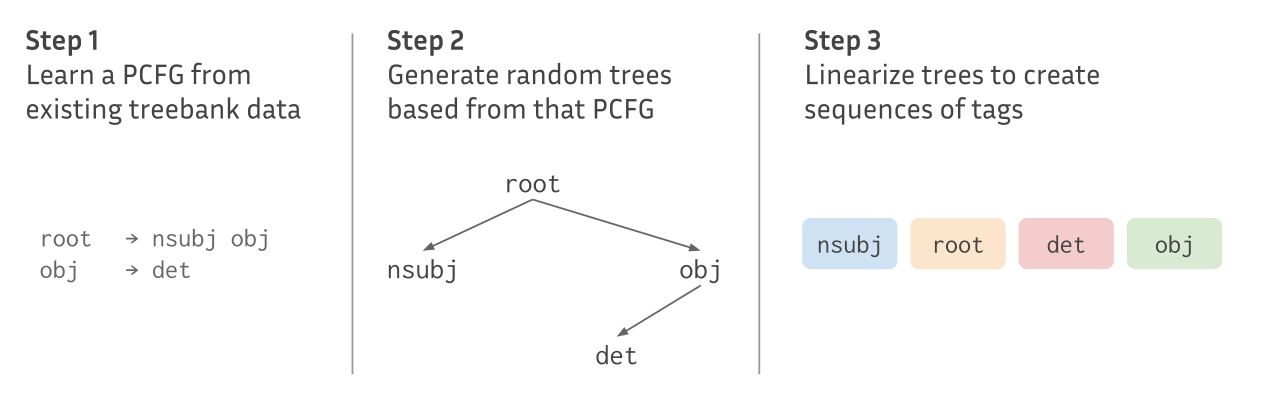

To create artificial structure, we use dependency trees from the French GSD treebank to learn a Probabilistic Context Free Grammar (PCFG). Using this PCFG, we sample new trees that we linearize to form sequences. This process yields sequences of tags corresponding each to a dependency relation.

We then relexicalize these tags with items from a vocabulary chosen arbitrarily. We do not apply any other linguistically-inspired rules. Our goal is rather to construct data generated from an underlying structure than “natural-sounding sentences”.

Our first method for relexicalization (which we will call PCFG+Zipf) does not account for co-occurrences within sentences. We assign to each dependency relation a vocabulary size (computed using real statistics about that dependency relation) and a set of tokens of the corresponding size. We then relexicalize sequences of tags by drawing a token for each dependency relation from its set, using a Zipf law.

Inspired from Ri and Tsuruoka [6] we also try another method (PCFG+loglinear) for linearization which aims at enforcing a notion of context. We create vocabulary sets for each dependency relation similarly to the PCFG+Zipf method. Every token from each set is assigned a random embedding vector $v_s \in \mathbb{R}^d$. Then, for each sequence of tags, we randomly draw a “topic vector” $v_t\in \mathbb{R}^d$ and sample for each dependency relation a vocabulary element $w\in S_{tag}$ according to the following distribution:

$$ p(w|t) = \frac{\exp(v_w \cdot v_t)}{\sum_{s\in S_{tag}}\exp(v_s \cdot v_t)} $$

Intuitively, the words that are similar according to their (random) embeddings will be often sampled together, thus creating a notion of co-occurrence within sentences.

For both methods, we generate a corpus of 1 million sentences, corresponding roughly to 15 million tokens. We use a total vocabulary size of 5000 elements and keep only the 20 most used dependency relations when constructing the PCFG.

The Baselines

The Language Model representations are surprisingly robust to new modalities and languages. Thus, previous works have for instance recycled models to create new ones in languages with fewer data [4] or added languages to multilingual models after training [5].

Our baseline is similar. We use the same setting described earlier to train a model on English OSCAR data, then re-initialize its embeddings and retrain it on Breton data. This is a particularly efficient baseline compared to pretraining from scratch.

As a control and to test the influence of the source language on the transfer, we train Language Models on Czech and Turkish. They belong to different language (sub)families than Breton and have different syntax.

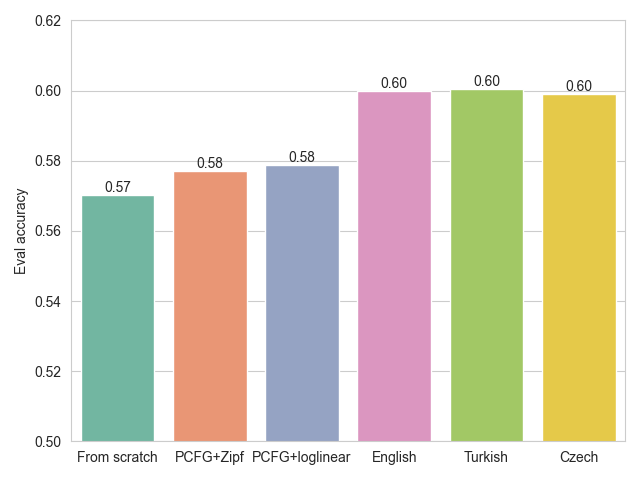

As we will see later, the three models (English, Czech and Turkish) transfer to Breton with almost the same accuracy, demonstrating a very moderate impact of the source language syntax on the final representations.

Results

We present in the following graph the MLM evaluation accuracies obtained by each of the models on the OSCAR Breton subset.

The models trained on synthetic data fail to significantly improve on a model trained from scratch on Breton. The models pretrained on natural language however improve by roughly 3 accuracy points compared to pretraining from scratch. Adding a level of co-occurrence (the PCFG+loglinear model) did not seem to help the transfer.

Maximum evaluation accuracy on the Breton Masked Language Modelling task using each of the different source pretraining methods. The x-axis corresponds to the source pretraining data. “From scratch” was initialized randomly before the target pretraining.

In the following section, we look at a few questions that arose when trying to understand what may be the cause of the different transfer accuracies.

Analysis

In the process of trying to design a better synthetic language and understanding the source of failure when transferring to a target (natural) language, we came across a few interesting questions and experiments that we detail here.

How important are position embeddings in the transfer?

We transfer two types of modules when pretraining on the target language, Breton: the Transformer layers and the positional embeddings. Although we reason mostly around the Transformer layers as encoding structure in our sentences, we may be diminishing the importance of good positional embeddings trained on natural data.

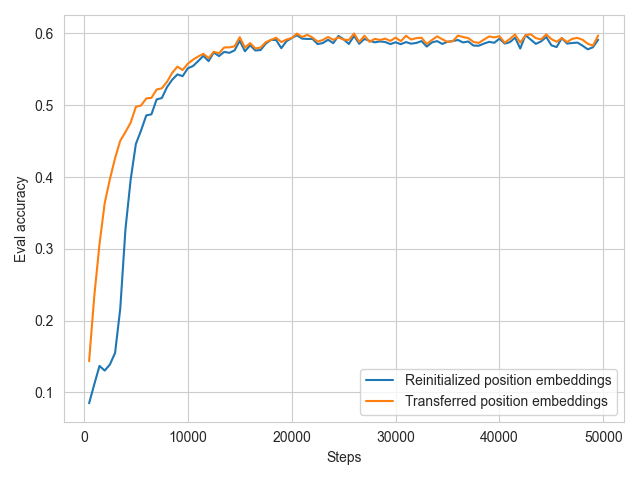

To test this effect, we reset the positional embeddings at the beginning of pretraining on the target language and look at the validation accuracy.

Evaluation MLM accuracy during target pretraining on Breton using the English pretrained model.

We can see that re-initializing the positional embeddings only delays training for a few steps, but does not impact the final performance. The same effect appears for a model trained using artificial data. From that experiment, we concluded that the Transformer layers are mostly responsible for the transfer to the target language.

How different are the models trained with artificial data and natural language data?

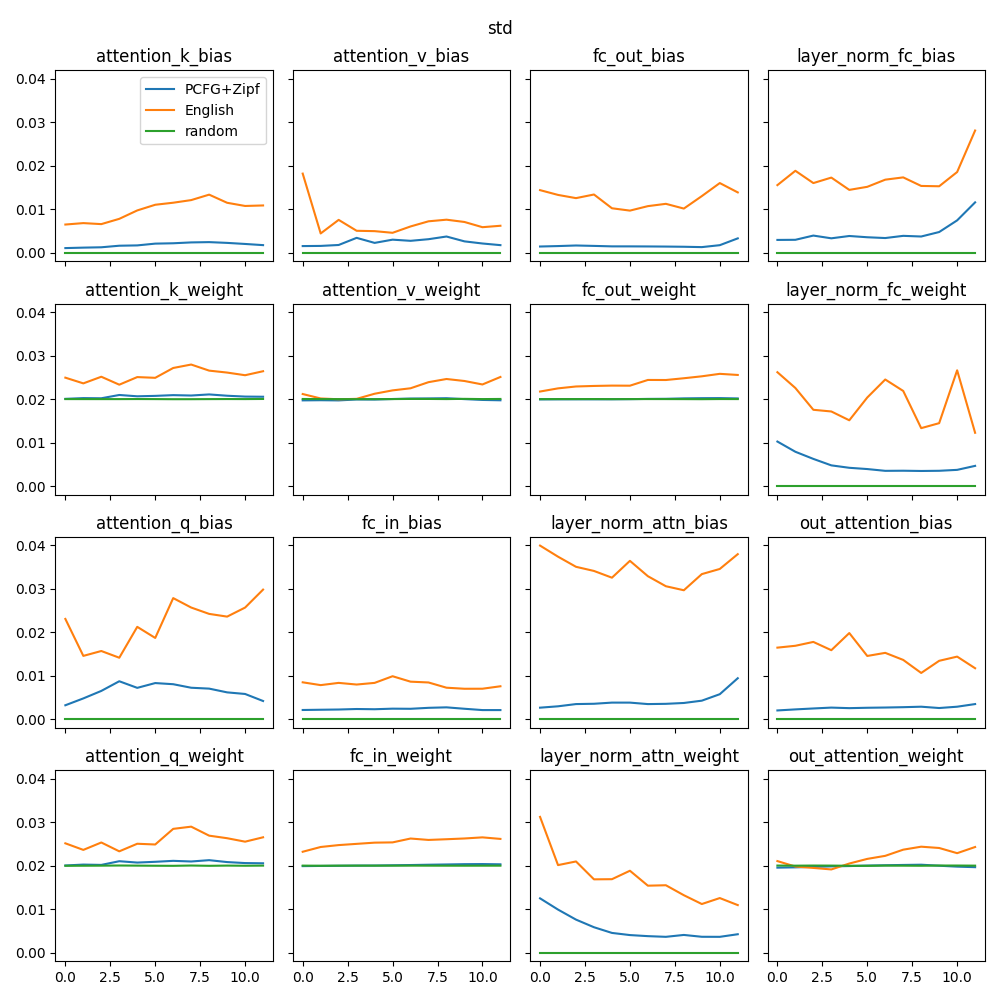

The models trained on different modalities transfer with very different accuracies to the target language. Can we identify some statistics in the model parameters that correlate with a better transfer performance? To answer this question, we looked at the mean, standard deviation and maximum parameter values of every layer and every module in our models. The average weight values give very little information, as both types of models (trained on natural or synthetic data) have similar statistics.

The standard deviations are quite different, however. Despite being trained with the same hyperparameters, the models trained on natural data exhibit larger standard deviations than the models trained on artificial data, which stay closer to the standard deviation set at initialization. The following graph shows the standard deviations of weights and biases from every module.

Standard deviations of each module parameter values. The x-axis corresponds to the layer being studied, and “random” corresponds to a randomly initialized (un-trained) model.

Are higher standard deviations a key to transfer performance, or merely an artefact of natural language pretraining? The answer to this question remains unclear, yet these statistics hint at a possible issue with the artificial model. Indeed, since its parameters do not deviate by a lot from their original values, the task may be learnt by something else than the Transformer layers.

Is the artificial task learnt only in the embeddings?

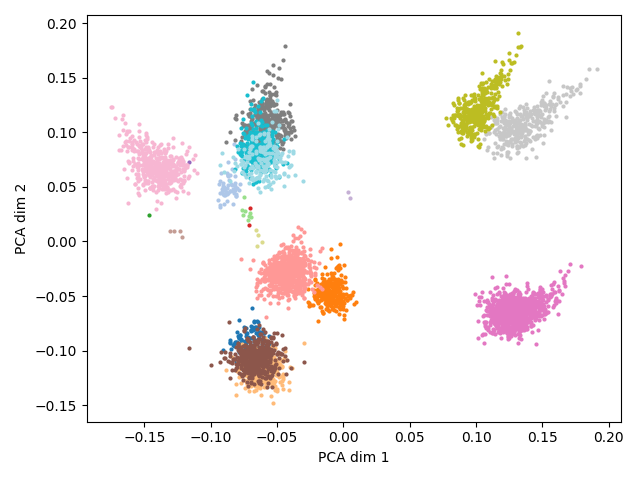

We take a look at the word embeddings of the PCFG+Zipf model by projecting them on a 2D space using a PCA.

PCA projection on a 2D plane of the word embeddings from the artificial model. Each point has a color corresponding to its dependency relation tag. Some clusters are larger than others because the number of vocabulary elements assigned to a dependency relation is a function of the number of unique lemmas corresponding to that relation in the real data.

As we can see, the embeddings are pretty well clustered by dependency relations. This is expected in part because knowing precisely what relations surround a masked token is the only way to predict correctly the masked dependency relation. However, we want the model to rely on the Transformer layers rather than the embeddings to solve the task since we throw away the embeddings at the end of the artificial pretraining.

To enforce this behaviour, we retrain our model on artificial data but freeze the embeddings during pretraining, forcing the model to rely entirely on the position embeddings, Transformer layers and language modeling head. Interestingly, the resulting model parameter values have slightly higher standard deviations than before, indicating that it may be the Transformer layers taking over to solve the task. However, the target pretraining on Breton leads to the same accuracy as before.

It is plausible that our artificial task is learnt by the embeddings, yet solving this issue is inconclusive. The problem may reside in the task itself.

Can we scale the size of our artificial dataset?

The synthetic dataset is relatively small compared to the natural language datasets we use, which may explain why we fail to transfer. However, increasing the dataset size from 15 million tokens to 744 million tokens did not improve the performance, neither during the artificial pretraining (the losses are similar in both cases) nor on the target pretraining.

This may be a clue toward a missing ingredient in our synthetic dataset, since scaling a natural language dataset should result (until a certain limit) in improved performance. The task may be either too easy or too hard to solve, resulting in a plateau in the model performance.

Conclusion

Despite our best efforts to incorporate some key characteristics of natural language in our synthetic dataset (a structured way of generating sequences and a notion of co-occurrence of tokens), we were unable to induce biases in the Transformer network that would transfer to the pretraining on a target language with smaller resources. However, we believe this is rather due to our artificial language being ill-defined than the impossibility of transferring useful capabilities to Language Models without using real data, as previous works have shown such transfer for other tasks.

References

[1] Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models, Hoffmann et al., 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.15556

[2] Does Pretraining for Summarization Require Knowledge Transfer?, Krishna et al., 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.04953

[3] Learning Music Helps You Read: Using Transfer to Study Linguistic Structure in Language Models, Papadimitriou and Jurafsky, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.14601

[4] Embedding Recycling for Language Models, Saad-Falcon et al., 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.04993

[5] When Being Unseen from mBERT is just the Beginning: Handling New Languages With Multilingual Language Models, Muller et al., 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.12858

[6] Pretraining with Artificial Language: Studying Transferable Knowledge in Language Models, Ri and Tsuruoka, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.10326